Article: GPU Driven Rendering

An overview of how GPU driven rendering works in my renderer.

Overview

Hello! In an effort to document the path towards my current renderer design, I decided to write this article explaining the high-level details and design decisions I’ve made over the course of the project. If you are a prospective employer, this should serve as evidence that I do, in fact, know what I’m talking about (at least a little bit). For everyone else, hopefully you glean some useful bits from this article that you can incorporate into your own renderers. I’m going to be glossing over some super nitty-gritty details and just go over the important stuff that should give you a general idea for how everything fits together.

I’m going to assume you know at least the fundamentals of computer graphics (the render pipeline, buffers and textures, shaders, draw calls, etc.) and compute shaders, as well as common terminology and data structures (mesh, material, model matrices, etc.) So, this is geared towards people who either know more than me, or have written a basic renderer already and want to see what I’ve done.

My renderer and engine are written in Rust, but don’t worry. I’ll explain any Rust specific weirdness as we go so if you’re used to using C or C++ (most of you, I’m guessing) you’ll understand what I’m doing. I’m also using Vulkan for the graphics API, so I’ll be using its terminology.

Part 1: The Worst Renderer

Obviously, the best place to start is rock bottom (that way, we can only go up!) A very naive renderer might look something like this.

// This is a member function for the renderer that does the actual rendering.

//

// It takes in a command buffer we can write to and a list of renderable objects (the type with

// brackets is called a slice. It's like a C array that we also know the length of).

fn render(&self, cmd: &mut CommandBuffer, objects: &[Renderables]) {

// We iterate over each object sequentially...

for obj in objects {

// Bind all associated resources...

obj.bind_material(cmd);

obj.bind_mesh(cmd);

obj.bind_model_matrix(cmd);

// Then issue a draw call.

obj.draw(cmd);

}

}

This sucks really bad. First, you have to realize something about how graphics APIs (the command buffer here, specifically) work. They’re essentially big state machines. So, if you bind a resource with one function call, you’ve set up the state for future calls to use that resource. Second, you have to realize that it’s very bad for performance to be switching state all the time. Pipeline swaps (i.e. changing materials) are especially bad for performance since they contain an enormous amount of state.

With that in mind, it becomes obvious that it’s probably a bad idea to bind materials and meshes every time we render a new object. Instead, it would make sense to first sort our draw calls somehow so that we can minimize the amount of times we need to change state. That brings us to…

Part 2: Sorting Your Draw Calls

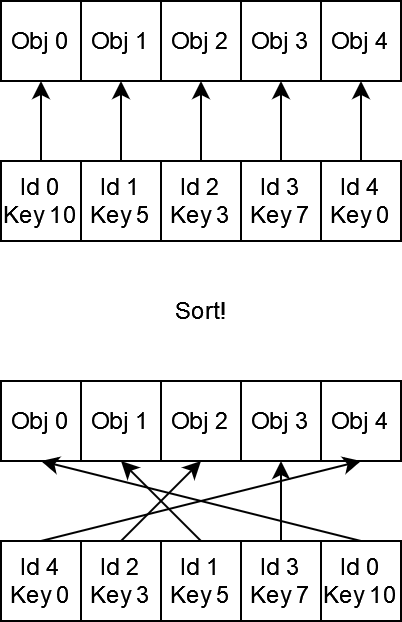

This is the first step on a long journey to making a fast renderer. As with any first step, it’s arguably the most important, so it’s a good idea to get this right the first time. There are many ways you can go about sorting your draw calls around, but my favorite is inspired by this blog post by Christer Ericson. The idea is pretty simple. We can pack the information needed to draw an object into a tuple: one element contains a compact representation of all the state needed to perform the draw call, and the second element contains an index into a big array with all our per-object data (think model matrices.) We can put these tuples into an array, and then sort the array based on the draw state info. That means our list of draw calls ends up looking something like this:

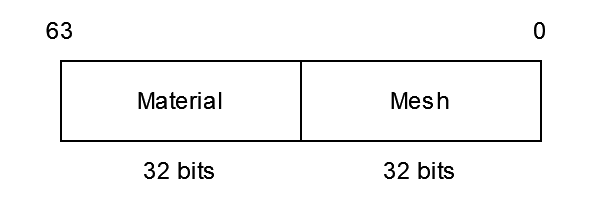

Christer recommends packing the draw call data into an integer, and I’m inclined to agree for a few reasons:

- Sorting integers is fast.

- It makes it easy to experiment with how we want to sort our draw calls. Should changing materials be more expensive than changing vertex data? Probably yes, so put the material ID in the higher bits of the integer. Maybe we’re feeling daring today, so we swap them around and sort with vertex data in the most significant bits.

- Related to point 2, it makes it easy to add new features that might impact draw call sorting. We just have to reserve bits in the integer for it!

Here’s an example of what one of these “draw keys” looks like:

To take advantage of the fact that our draw calls are now sorted, we have to change how our render loop works. The way Ard Engine handles this is by keeping track of the currently bound state ourselves (the draw key) and then rebinding using the API whenever we detect a change in pipeline/mesh/etc.

Our new render loop looks something like this:

// Each object is represented with this structure.

struct DrawId {

// The key we're sorting by.

key: u64,

// The "id" of the object is really just its offset in the main object data array.

offset: usize,

}

fn render(&self, cmd: &mut CommandBuffer, objects: &[Renderables]) {

self.ids.clear();

// This is just letting us iterate over `objects` while also getting the associated index for

// the object we're currently looking at.

for (i, obj) in objects.iter().enumerate() {

self.ids.push(DrawId {

key: obj.make_key(),

offset: i

});

}

// Specify we want to sort based on the draw key

self.ids.sort_unstable_by_key(|draw_id| draw_id.key);

// Now we can draw our objects!

let mut cur_draw_state = DrawState::default();

for id in &self.ids {

// Remember that our draw id points into `objects` using the offset field.

let obj = &objects[id.offset];

// This only rebinds when it detects that a state change has occurred

cur_draw_state.check_for_rebinds(cmd, id.key);

// The model matrix changes for each object, so we have to rebind it every draw call

obj.bind_model_matrix(cmd);

obj.draw(cmd);

}

}

With the foundation in place, we can start looking at the really cool stuff.

Part 3: Instance Everything

“Gee, author,” you might be saying to yourself right now. “It’s cool that we sorted our draw calls and everything, but we still have to rebind our model matrices every draw. That’s kind of lame, tbh.” I agree! It is pretty lame, but we have a solution. First consider the following scenario.

We are trying to draw a forest. Forests are nice, right? Now, since most people are not graphics programmers and thus will not scrutinize every detail of the graphics of our game, we can get away with using only a handful of tree models, and just distributing them randomly over our scene with some random rotation and scale added in for good measure.

Image from the Steam page for Firewatch by Campo Santo. Notice how the highlighted trees all have the same markings on them? That’s because they’re instanced, but you probably wouldn’t notice it during gameplay unless you were looking for it.

Image from the Steam page for Firewatch by Campo Santo. Notice how the highlighted trees all have the same markings on them? That’s because they’re instanced, but you probably wouldn’t notice it during gameplay unless you were looking for it.

This is a good idea in principle, but with our current renderer we’ll quickly come to realize we can’t get enough trees on screen to fill the forest! We’ve got too many draw calls, and we’re spending too much time on the CPU submitting them. Wouldn’t it be nice if we could somehow say “draw 1000 trees” but in one draw call instead of one-thousand?

You can! It’s called instanced draw calls and it works exactly how I described it. You can just pass in an instance count into the draw call and it will draw that many instances. Additionally, most APIs will let you pass in a “first instance” which is a sort of base offset for the instance ID. To use the instance ID in Vulkan, you use gl_InstanceIndex in your GLSL shaders. The value of gl_InstanceIndex is firstInstance + i where i is the index of the current draw call.

This is nice and all, but we’ve got a problem still. How do we know how many instances we need to draw. Also, how does this even help us solve the problem of having to rebind the model matrix every draw call? Both excellent questions.

Grouping

First, consider what the requirements are for instanced draw calls. Since the draw call is using the previously bound state, we can’t change the pipeline (material) and vertex data, but we want to somehow change the model matrices. If we go back and consider our draw key for a moment, we’ll realize that the state we don’t want to change is actually encoded in the draw key. How convenient!

With that in mind, it becomes obvious that we can use instancing to render objects with the same draw key together. You might also remember that we sorted our draw calls based on the key. That means that objects with the same key are grouped together in the self.keys array for us already. We just need to define these “groups” like so.

// We can represent contiguous groups of objects using this structure.

struct DrawGroup {

// The key that each draw ID shares.

key: u64,

// How many draw IDs are in the group.

len: usize,

}

fn render(&self, cmd: &mut CommandBuffer, objects: &[Renderables]) {

// ... Create and sort keys as before ... //

self.groups.clear();

// NOTE: You should make sure ids is not empty :)

let mut cur_key = self.ids[0].key;

self.groups.push(DrawGroup {

key: cur_key,

len: 0

});

// We loop over our generated keys and make groups

for (i, key) in self.keys.iter().enumerate() {

// If the key changes, it means we're looking at a new group

if key != last_key {

cur_key = key;

self.groups.push(DrawGroup {

key: cur_key,

len: 0

});

}

// Update the draw count

let group_idx = self.groups.len() - 1;

groups[group_idx].len += 1;

}

// ... Rendering ... //

}

Per-Object Data

The last obstacle is now per-object data (model matrices). The solution is very similar to the solution to literally every other problem we’re going to be looking at in the rest of this article, so pay attention! The idea is we use something in Vulkan called a Shader Storage Buffer Object (SSBO). They’re similar to Uniform Buffer Objects (UBO) except that they can be written to inside a shader and (most important for us) can be much larger than UBOs.

We’re going to use them in a way that might seem a little silly at first, but trust me that it will make sense by the end of the article. Specifically, when we get to the last part on culling.

We’re going to use two SSBOs. The first is going to hold per object data. This data will be in the same order as the objects come in from our objects list. The second is going to be a list of indices that point into the first SSBO. Generating these buffers looks something like this.

// This structure holds our per object data sent to the GPU.

struct ObjectData {

// Right now, it just has the model matrix.

model: Mat4,

}

fn render(&self, cmd: &mut CommandBuffer, objects: &[Renderables]) {

// Upload per object data to the GPU

for (i, object) in objects.iter().enumerate() {

// Pretend that `object_data_ssbo` is like an array and we

// can write at any index `i` we want.

self.object_data_ssbo.write(i, ObjectData {

model: object.model_matrix(),

});

}

// ... Draw call sorting and grouping ... //

// Write in the object indices. Remember that offset field in `DrawId`? Well, it maps directly

// to the object data ssbo we just made!

for (i, draw_id) in &self.ids {

self.object_idxs_ssbo.write(i, draw_id.offset as u32);

}

// ... Rendering ... //

}

Putting It Together

We now have the right setup to do instanced rendering, so let’s take a look. Also, our render loop is getting really big, so let’s separate this out into two functions.

fn prepare_draws(&self, objects: &[Renderables]) {

// ... Upload per object data. ...

// ... Create and sort draw IDs. ...

// ... Create draw groups. ...

// ... Upload object IDs. ...

}

fn render(&self, cmd: &mut CommandBuffer) {

let mut cur_draw_state = DrawState::default();

// Wow! We can bind our model matrices for every object one time!

self.bind_object_data();

self.bind_object_idxs();

let mut draw_offset = 0;

for group in &self.groups {

cur_draw_state.check_for_rebinds(cmd, group.key);

cmd.draw_indexed_instanced(

group.len, // This is the `instanceCount`

draw_offset, // This is the `firstInstance`

);

draw_offset += group.len;

}

}

The lookup for per object data in your shaders looks something like this. In case it’s not clear how this is working, refer back to the diagram in Part 2 showing sorting by draw key. It’s essentially the same kind of lookup.

// `ObjectData` is held in the `object_data` SSBO.

// The indices mapping into `object_data` are held in the `object_idxs` SSBO.

void main() {

uint idx = object_idxs[gl_InstanceIndex];

mat4 model = object_data[idx];

gl_Position = camera.projection * camera.view * model * IN_POSITION;

}

That’s pretty cool! We’ve gotten our renderer to instance everything for us automagically! However, you might be surprised to hear that we’re only halfway to perfect.

Part 4: Unified Vertex Memory

This idea that we can pack related things together into big buffers and bind them once (or as few times as possible) turns out to be a real life super power. We will extend this idea to vertex data next.

In our current renderer, each mesh gets its own vertex and index buffers. This sucks. What, we have to rebind vertex data every time we change meshes? Lame. But, remember we have a super power! What if we packed the vertex data for every mesh into a handful of BIG vertex and index buffers? As it turns out, this is possible.

Vertex Layouts

The first step is to consider what kinds of meshes we’re going to be working with. I wanted my engine to be flexible enough to handle pretty much anything I could throw at it, so this is what I came up with. First, each mesh has a “vertex layout” which are some bit flags that indicate which vertex attributes the mesh has. More attributes can be added to the layout as needed.

// This "bitflags!" thing is a handy library that auto-generates the boilerplate needed to do

// bitflags in Rust.

bitflags! {

struct VertexLayout {

// NOTE: I don't include positions in the vertex layout since I require all meshes to

// contain positions.

const NORMALS = 0b0000_0001;

const TANGENTS = 0b0000_0010;

const COLORS = 0b0000_0100;

const UV0 = 0b0000_1000;

const UV1 = 0b0001_0000;

const UV2 = 0b0010_0000;

const UV3 = 0b0100_0000;

const ATTRIBUTE_COUNT = 8;

}

}

Then, I have a mapping from each vertex layout to an allocator dedicated to making meshes for that layout type.

// Holds all mesh data.

struct MeshAllocators {

layout_to_allocator: HashMap<VertexLayout, MeshAllocator>,

// All meshes can share the same index buffer (woah!)

index_buffer: BufferAllocator,

// ...

}

// Responsible for allocating the vertices of a mesh with a particular vertex layout.

struct MeshAllocator {

/// Elements are `None` if this allocator doesn't support the particular attribute.

vertex_buffers: [Option<BufferAllocator>; VertexLayout::ATTRIBUTE_COUNT],

// ...

}

// Responsible for sub-allocating indices or a single kind of vertex attribute within a buffer.

struct BufferAllocator {

// ...

}

Since meshes can have any number of possible vertex and index counts, I use a simple buddy memory allocator to allocate vertex and index data. This has the added benefit of being deterministic. This means if we’re allocating for a single vertex layout, the state of each allocator in the vertex_buffers array is the same. If one allocator fails, they’re all going to fail. Most importantly, it means the offsets (in multiples of the element size) are the same for each mesh. In other words, you can imagine that each allocator is an array of elements of the type of the attribute (Vec4 for positions, normals and tangents, Vec2 for UVs). If we allocate a mesh and one of the allocators says “your positions start at index 64”, then we know every other attribute will also start at index 64 within its respective allocator.

This is important for rendering since pipelines don’t want your vertex data to be all jumbled up and out of order (i.e. it would throw a fit if positions were at index 64 but, say, UVs were at index 1024).

Rendering With The Buffers

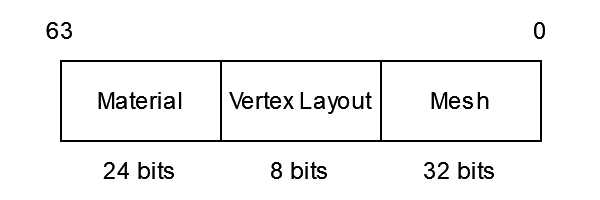

So, how do we use this new unified vertex memory? Do you remember our draw keys? Well, we can pack the vertex layout of a mesh into the bits of the draw key! Didn’t I tell you it would be easy to add new features? To figure out where in the draw key we should put it, consider this: if two draws have different meshes, but the same vertex layout, we don’t need to rebind vertices after drawing one of them. However, if the vertex layout does change, we do need to rebind the vertices. This tells us that the vertex layout is more important than the particular mesh, so we’ll fit it in between the bits for the material and the bits for the mesh like so:

Now, during rendering when we call cur_draw_state.check_for_rebinds we don’t check if the current mesh has changed but instead check if the vertex layout has changed. Additionally, we have to update our draw command to look something like.

// Remember that we encoded the meshes ID in the key, so we can extract `cur_mesh` from that.

cmd.draw_indexed_instanced(

// This is the `instanceCount`.

group.len,

// This is the `firstInstance`.

draw_offset,

// The base index of the block for the index allocation for the mesh.

cur_mesh.index_base,

// The base index of the block for the vertex allocation. Remember that each vertex

// allocator is going to give us the same block, so we just pick an arbitrary one to use.

cur_mesh.vertex_base

);

And with that, we have unified vertex memory. Next stop, materials and textures!

Part 5: Bindless Textures (and Materials!)

I want you, dear reader, to think about how we’re going to minimize the need to bind materials and textures. Go on. I’ll wait…

If you guessed, “we’re going to put everything into a big buffer” then you’d be correct! Doing this with textures is often called “bindless textures,” but I think it’s more appropriate to call it “bind-less” since you still need to bind the textures. Just… Less often. In fact, everything we’ve been doing up to this point could be considered “bindless design” since we’re trying to minimize the amount of binding that we need to do.

Textures

First, let’s consider our textures. We don’t want to bind them each time we use a material, so let’s put all the textures into a big array and then bind it once. Yes, it’s really that easy. This article by Gabriel Sassone goes into detail on how you do this in Vulkan, and it’s essentially the same thing I do in my engine.

The only downside is that it puts an upper limit on the number of textures you can have in memory at a single time, but you can choose a high enough number based on your use case. My renderer currently uses a texture count of 2048. Each texture is given an ID which maps directly to its index in the array. Now, instead of binding textures we bind the index of the texture (deja vu?)

Materials

Second, let’s consider our materials. As of now, we’ve been treating the pipeline and material as the same thing, but in reality they’re separate concepts. In my engine a Material is like the pipeline. It’s the set of shaders and pipeline state to perform rendering. For example, I have a single PbrMaterial that pretty much every object uses. I also have a MaterialInstance structure which, as the name implies, is a particular instance of a material. So, I might have one PbrMaterial but I might have a brick MaterialInstance and a grass MaterialInstance and a glass MaterialInstance, etc. The MaterialInstance holds onto the “data” for a material (for PBR this is roughness and metallic factors, an alpha cutoff, and a color factor) and the indices for the textures (color, normal maps, metallic/roughness mask, etc).

So, what I did was make a very simple slab allocator/object pool with a free list for deleted material instances. It looks something like this:

struct MaterialBuffer {

// The actual SSBO.

buffer: Buffer,

// The size of a single slab.

data_size: u64,

// The number of slabs that can currently fit in the buffer.

cap: usize,

// Counter to give each slot an ID on allocation.

slot_count: usize,

// Free slots no longer in use.

free: Vec<usize>,

}

Textures use the same allocator, but have a fixed size to accommodate up to 8 textures per material.

Then, I have a material factory which looks something like this:

struct MaterialFactory {

// Keyed by the size of the material data slabs.

data_buffers: HashMap<u64, MaterialBuffer>,

texture_buffer: MaterialBuffer,

}

Each material instance allocates a slab from the data and texture buffers and holds onto them. One cool thing about this is that we aren’t keying by the “type” of material data, but instead the size in bytes of the data. This means that if two Materials coincidentally have the same data size, they share the same buffer. Neat!

Updated Rendering

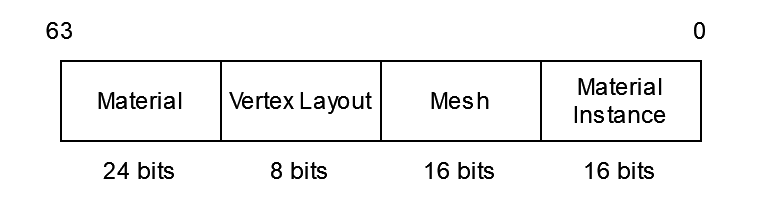

Now that we’ve got these buffers, we need to update some things about how we’re rendering. First, back to the draw key. Since the material instance is very unimportant now, we can reserve the lowest bits in the key for that, while the highest bits remain for the material:

Then we need to update cur_draw_state.check_for_rebinds to check if the material data size changes or the material itself changes (remember, not the material instance).

I would say most people would be very happy using the renderer as described thus far for their engines, but there is more we can do. In fact, it’s the namesake for this entire article and the thing that really makes bindless design shine.

Part 6: GPU Draw Call Generation

“Author,” You might be saying to yourself right now. “I don’t see how anything you’ve describe thus far is GPU driven rendering. Certainly it’s GPU oriented since it’s designed to make the GPU happy, but is the GPU really driving the rendering? I think not.” You, dear reader, are correct! Really nothing about what we’ve done so far is GPU driven, so let’s change that.

GPU driven rendering is really all about this idea: wouldn’t it be cool if the GPU could tell itself what to draw? The main bottleneck in basically every renderer is communicating information between the CPU and the GPU (draw calls in particular) so what if we just don’t? Or, maybe more realistically, do as little communication as possible. Bindless design helps with this idea, but it isn’t the full answer. What we really need is for the GPU to issue its own draw calls. I present to you…

This single command is what I would describe as the most powerful tool for performing GPU driven rendering. To understand how it works, let’s take a look at its parameters (By the way, we’re going to be looking at C functions now instead of Rust. These come straight from the Vulkan specification. We’ll go back to Rust in a bit.)

void vkCmdDrawIndexedIndirectCount(

VkCommandBuffer commandBuffer,

VkBuffer buffer,

VkDeviceSize offset,

VkBuffer countBuffer,

VkDeviceSize countBufferOffset,

uint32_t maxDrawCount,

uint32_t stride

);

The first thing you’ll probably notice is that, unlike vkCmdDrawIndexed, we don’t specify any index, vertex, and instance counts or offsets. What gives? Well, instead of providing that information in the arguments for the draw call, we provide them in a buffer! That buffer is an array of structs that look something like this:

typedef struct VkDrawIndexedIndirectCommand {

uint32_t indexCount;

uint32_t instanceCount;

uint32_t firstIndex;

int32_t vertexOffset;

uint32_t firstInstance;

} VkDrawIndexedIndirectCommand;

This struct has all the parameters we were expecting. You should also know that you can provide a custom stride for the draw calls in the buffer, meaning you could actually pack extra data into each draw call struct if you wanted. The number of draw calls that are sourced from the buffer is grabbed from the count buffer at countBufferOffset. It’s expected to be an unsigned 32-bit integer. The final draw count is equal to the minimum of the draw count grabbed from the buffer and the maxDrawCount argument.

The fact we can now source our draw calls from a buffer is HUGE, because it means we can generate the draw calls on the GPU using compute shaders. Specifically, we’re going to be doing culling on the GPU and outputting the draw calls that pass culling into those buffers we saw previously. VulkanGuide has a great article on this, except they use vkCmdDrawIndexedIndirect which doesn’t allow you to specify draw call counts in a separate buffer.

Binning Draw Groups

The first step is to “bin” our draw groups. What I mean by that is, I want to determine the sets of draw groups that I can get away with rendering all at once without having to rebind anything. More specifically, they all need to share the same vertex layout and material (again, remember by “material” I mean the equivalent of a pipeline). Luckily, we already have something that does that! Remember that DrawState struct we were using to check for rebinds? Well, as we’re looping over our groups, we can chuck them into bins and determine if we need a new bin by seeing if the DrawState told us that a rebind was required. The code looks something like this.

// Represents a contiguous set of groups that can be rendered with one draw indirect call.

struct DrawBin {

// The number of groups in the bin.

count: usize,

// The offset in the groups array for the start of this bin.

offset: usize,

// The material used by groups in the bin.

// `None` means the last bin's material is identical.

material: Option<MaterialId>,

// The vertex layout used by groups in the bin.

// `None` means the last bin's vertices are identical.

vertices: Option<VertexLayout>,

// The size of material data used by `material.`

// `None` means the last bin's data size is identical.

data_size: Option<usize>,

}

// The structure that the first compute shader is going to use to cull objects.

struct GpuDrawGroup {

// The number of instances to draw for this group.

instance_count: u32,

// The offset within the `object_data_ssbo` for the start of the objects in this group.

first_instance: u32,

// The index of the bin this group belongs in.

draw_bin: u32,

}

// The structure the second compute shader is going to use to generate draw calls.

struct GpuDrawBin {

// The number of groups in this bin.

count: u32,

// The offset in the groups buffer for the start of this bin.

offset: u32,

}

fn prepare_draws(&self, objects: &[Renderables]) {

// ... Create draw groups. ...

self.bins.clear();

let mut cur_draw_state = DrawState::default();

let mut draw_count = 0;

let mut draw_offset = 0;

let mut object_id_offset = 0;

for (i, group) in self.groups.iter().enumerate() {

// Checks if rendering the current group would require us to rebind anything. It only

// tells us exactly which bindings changed (material, vertices, or material data).

let delta = cur_draw_state.check_for_rebinds(group.key);

// If any of the bindings changed, a draw will be required

if delta.draw_required() {

self.draw_bins_ssbo.write(self.bins.len(), GpuDrawBin {

count: 0,

offset: i,

});

self.bins.push(DrawBin {

count: draw_count,

offset: draw_offset,

// Remember, this is the info for the previous bin.

material: delta.last_material,

vertices: delta.last_vertices,

data_size: delta.last_data_size,

});

draw_offset += draw_count;

draw_count = 0;

}

let first_instance = object_id_offset;

object_id_offset += group.len;

self.draw_group_ssbo.write(i, GpuDrawGroup {

// This starts at 0 since the GPU is going to determine how many instances to draw.

instance_count: 0,

first_instance,

draw_bin: self.bins.len(),

});

draw_count += 1;

}

// NOTE: You need an extra check down here for the final bin

// ... Upload object IDs. ...

}

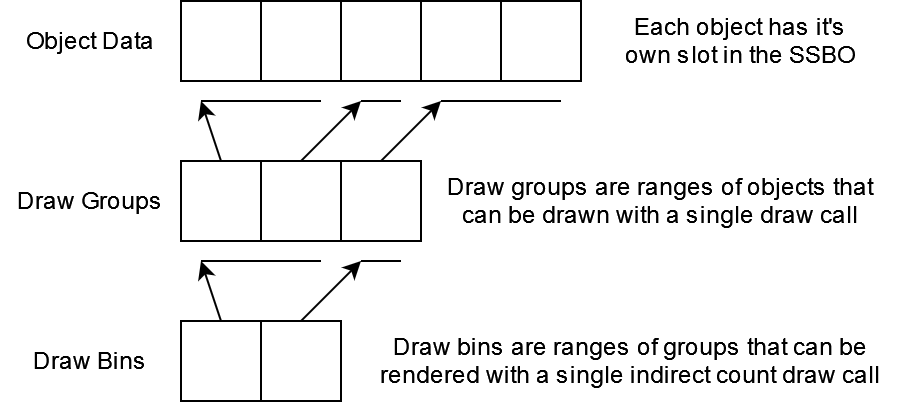

Ok… That’s kind of a lot and it might be hard to sort of wrap your head around what this is doing, so let me show you a diagram. This shows the relationship between object data, draw groups, and draw bins.

Generating Draw Calls

Now that we have our groups on the GPU in an SSBO, we can use a compute shader to do culling and then generate the actual draw calls. I’m going to gloss over the particular flavor of culling my engine uses since I plan on writing a separate article about it, but just know that it’s a combination of frustum and occlusion culling.

Do you remember the object_idxs_ssbo that we made earlier? The one that I said might seem silly but will make sense later? This is why we need it. That buffer is going to be one of the outputs of our culling compute shader. Instead of writing in the IDs directly, we can let it be undefined to start, and we can make a new buffer that I’ll call object_ids_ssbo that contain this per object info:

struct GpuObjectId {

data_idx: u32,

group_idx: u32,

}

So, again, the idea is that each object we want to render has one of these IDs. The data_idx points into the big object_data_ssbo so we can get per object data, and group_idx points into the draw_group_ssbo that we just made so we can determine what group (draw call) the particular object belongs to. Finally, we can write the compute shader that does culling. The basic idea is that we’re dispatching over the objects and then updating the instance counts in their associated group if they pass culling.

void main() {

uint object_idx = gl_GlobalInvocationID.x;

if (object_idx >= object_count) {

return;

}

// Magical culling!

if (is_culled(object_idx)) {

return;

}

GpuObjectId object_id = object_ids_ssbo[object_idx];

// If the object passes culling, we update it's associated groups instance count and write

// the index of the object into the output idx buffer

uint object_offset = atomicAdd(draw_group_ssbo[object_id.group_idx].instance_count, 1);

uint instance_idx = draw_group_ssbo[object_id.group_idx].first_instance + object_offset;

object_idxs_ssbo[instance_idx] = object_id.data_idx;

}

Compacting Draw Calls

Nice, so now we’re generating the object_idxs_ssbo in a compute shader, but we still need to actually generate the indirect draw calls. We do this in a second compute shader that dispatches over the draw groups. If the instance count is greater than 0, we write the actual draw call into a draw_calls_ssbo that has the VkDrawIndexedIndirectCommands.

void main() {

uint group_idx = gl_GlobalInvocationID.x;

if (group_idx >= group_count) {

return;

}

GpuDrawGroup group = draw_group_ssbo[group_idx];

// If there are no draw calls, we can ignore this group

if (group.instance_count == 0) {

return;

}

// Otherwise, we update the draw bins count and write in the bin.

uint group_offset = atomicAdd(draw_bins_ssbo[group.draw_bin].count, 1);

uint bin_base = draw_bins_ssbo[group.draw_bin].offset;

// Make the draw call...

draw_calls_ssbo[bin_base] = ...

}

Ok… So, you might’ve noticed that I left out the actual writing of the draw call. That’s because I realized while writing this there are two ways you could go about doing it. What you need to create the draw call is information about the mesh (the index count, first index, and vertex offset). You could either store those in the GpuDrawGroup or you could have a separate SSBO that has every mesh’s vertex offset and index offset/count information and just store mesh IDs in the draw group. Using a separate SSBO will allow you to write less data per group from the CPU to the GPU per frame, but with the added cost of an extra layer of indirection, so pick your poison. I opted for a separate SSBO.

Rendering With Indirect Count

Finally… FINALLY! We can update our render loop to use these buffers! I’m going to skip over what the dispatches look like since they should be pretty obvious given the descriptions and comments. We’ll skip straight to the good stuff. So, here it is:

let mut cur_draw_state = DrawState::default();

self.bind_object_data();

self.bind_object_idxs();

let mut draw_offset = 0;

for (i, bin) in self.bins.iter().enumerate() {

// The same information we used to store in draw keys is now contained in bins.

// We check for changes in material, vertex layout, or material data size.

cur_draw_state.check_for_rebinds(cmd, bin);

cmd.draw_indexed_indirect_count(

// The draw calls buffer we're sourcing

&self.draw_calls_ssbo,

// The offset for the beginning of the draw calls in this bin.

bin.offset * std::mem::size_of::<VkDrawIndexedIndirectCommand>(),

// The draw counts buffer. Remember: the count is the first element in the bin struct.

&self.draw_bins_ssbo,

// the offset within the "counts" buffer.

i * std::mem::size_of::<GpuDrawBin>(),

// The maximum number of draw calls.

bin.count,

// The stride in bytes for each draw call.

std::mem::size_of::<VkDrawIndexedIndirectCommand>()

);

}

Conclusion

And that, ladies and gentleman, is the whole thing. If you read it all, congratulations! If you forgot half of it already, I don’t blame you! With this system, you can get pretty crazy frame rates with TONS of objects in your scene. If you’re only using a single vertex layout and material type, you can even render an entire scene in a single indirect draw call. For example, I often use the exterior Amazon Lumberyard Bistro scene for testing. I can render five separate instances of it without dipping below 10 ms frame times, and even then after checking the performance using Nsight Graphics, the limiting factor is actually the vertex shader because I don’t have a LOD system set up. In less vertex shader intense tests, I’ve been able to get it to handle upwards of a million instances hovering around 5 ms frame times.

As I stated at the beginning of this article, there are some details I left out for the sake of brevity. One example is that the large majority of scenes are typically static objects, so you can actually upload those objects one time instead of rewriting them every frame. Another thing, which I will mention as a definite downside, is that if you want transparent objects to look correct, you can’t use this system as is. The problem is that transparent objects need to be rendered back to front in order to look correct, and doing GPU culling and draw binning will destroy that ordering. You could do sorting on the GPU, but if you know anything about GPU sorting you’ll know it should be avoided at all costs, lest you lose a part of yourself. Currently, I bypass the culling shaders for transparent objects all together.

There are still some things I plan on doing to make this system even better. Something I mentioned a couple paragraphs ago is a LOD system. That will probably involve having each object be associated with a set of groups (the different LOD levels) and selecting which group to insert itself within based on screen size or distance from the camera. You might even be able to ditch the culling shaders all together if you used mesh shaders which can do culling themselves. However, mesh shader coverage isn’t exactly where I’d like it to be right now, so I may have separate code paths for the traditional pipeline and mesh shaders.

Thanks for reading! If there are any mistakes you spotted, or you have any questions, please feel free to email me.